Cardiovascular Response in Partly Mechanized Willow Planting Operations Indicates a Low to Moderate Intensity of Work

doi: https://doi.org/10.5552/crojfe.2026.3801

volume: 47, issue: 1

pp: 11

- Author(s):

-

- Borz Stelian Alexandru

- Bilici Ebru

- Article category:

- Original scientific paper

- Keywords:

- planting operation, tasks, short rotation willow crops, physical strain, cardiovascular workload, ergonomics, cohort study

Abstract

HTML

Fast growing species such as willow have been found to be a viable alternative for bio-energy production. Establishment of willow crops requires a series of operations, among which planting is important for their success. Partly mechanized planting has been studied lately in terms of productivity and costs, and it was found to be a viable alternative for small and dispersed plots. However, no research has addressed its suitability in terms of work intensity. One important assumption is that physical strain would be higher in such operations, mainly due to an intense use of the upper limbs, probably leading to a high cardiovascular workload. This study evaluated the level of physical workload in partly mechanized willow planting operations by heart rate measurements taken on six subjects, which were observed during all the common planting tasks. Close to 65 hours of observations were taken at a rate of one second, and the heart rate increment was used as the main indicator to characterize the workload of planting work. The findings indicate that there was a task-based variability in cardiovascular response (ca. 87 to 96 bpm) and in the heart rate increment among the subjects (ca. 14 to 28%). In addition, there was a differentiation in terms of heart rate increment among the planting tasks. Nevertheless, most of the data indicated a low to moderate cardiovascular workload. Although these results validate partly mechanized planting as a suitable alternative in terms of cardiovascular output, future studies should evaluate other ergonomic conditions such as the biomechanical exposure and the risks of developing musculoskeletal disorders.

Cardiovascular Response in Partly Mechanized Willow Planting Operations Indicates a Low to Moderate Intensity of Work

Stelian Alexandru Borz, Ebru Bilici

https://doi.org/10.5552/crojfe.2026.3801

Abstract

Fast growing species such as willow have been found to be a viable alternative for bio-energy production. Establishment of willow crops requires a series of operations, among which planting is important for their success. Partly mechanized planting has been studied lately in terms of productivity and costs, and it was found to be a viable alternative for small and dispersed plots. However, no research has addressed its suitability in terms of work intensity. One important assumption is that physical strain would be higher in such operations, mainly due to an intense use of the upper limbs, probably leading to a high cardiovascular workload. This study evaluated the level of physical workload in partly mechanized willow planting operations by heart rate measurements taken on six subjects, which were observed during all the common planting tasks. Close to 65 hours of observations were taken at a rate of one second, and the heart rate increment was used as the main indicator to characterize the workload of planting work. The findings indicate that there was a task-based variability in cardiovascular response (ca. 87 to 96 bpm) and in the heart rate increment among the subjects (ca. 14 to 28%). In addition, there was a differentiation in terms of heart rate increment among the planting tasks. Nevertheless, most of the data indicated a low to moderate cardiovascular workload. Although these results validate partly mechanized planting as a suitable alternative in terms of cardiovascular output, future studies should evaluate other ergonomic conditions such as the biomechanical exposure and the risks of developing musculoskeletal disorders.

Keywords: planting operation, tasks, short rotation willow crops, physical strain, cardiovascular workload, ergonomics, cohort study

1. Introduction

Fast growing species managed in short rotation by coppicing, such as willow, have been found to be a viable alternative for biofuel production (Ericsson et al. 2006, Mola-Yudego et al. 2010, El Kasmioui et al. 2012, Baker et al. 2022, Stolarski et al. 2023), and they have shown a high potential of saving the timber sourced by traditional forestry for other, higher value-added utilizations. In addition, such plantations may fulfill other functions and provide a diversified range of services (Kuzovkina and Volk 2009, Norbury et al. 2021, Zumpf et al. 2021, Livingstone et al. 2023a, Livingstone et al. 2023b). When it is aimed for biomass production, willow cultivation requires a series of operations whose intended goals are the establishment and improvement of biomass production, and valorization of biomass by harvesting (Dickmann 2006, Guidi et al. 2013). Planting willow is typically done by inserting small cuttings into the soil (Guidi et al. 2013), with the aim to establish a new crop by sprouting.

Currently, there is a variety of technical options used to plant a willow, many of them featuring a reasonable degree of mechanization (Guidi et al. 2013, Manzone and Balsari 2014, Bush et al. 2015, Manzone et al. 2017). Still, for small-scale applications, high investments in advanced machines developed for a particular functional goal, such as willow planting, may not be feasible since the plots used for crop establishment are typically small and dispersed (Borz et al. 2019a, Talagai et al. 2020), contributing this way to the increment of costs by a lower degree of machine utilization. In addition to reducing the costs, small farmers who are interested in diversifying their agricultural production are looking for flexibility in the equipment used.

Irrespective of the tools or machines developed and used, an important step is that of checking and eventually validating their sustainability in the area of ergonomics (Heinimann 2007, Marchi et al. 2018); this is typically done by studies aiming at checking and (re)designing a way of doing the work so as to be compatible with the human capabilities. While the scientific literature on economic and ecological efficiency of willow cultivation is quite well developed, there is a lack of studies describing the ergonomic condition in such operations (e.g., Borz et al. 2019b). As a general rule, a higher degree of mechanization is associated with improved safety and better ergonomics of the work, and may provide a better economic performance by enabling a higher productivity of work (Venanzi et al. 2023). In forestry and agriculture, for instance, manual planting operations involve considerable cardiovascular and musculoskeletal strains (Trites et al. 1993, Sullman and Byers 2000, Marogel-Popa et al. 2019, Patel et al. 2024). Research has identified these tasks as »hard continuous work« or »very heavy work« (Sullman and Byers 2000), with average working heart rates ranging from 97 to 135 beats per minute across different planting activities (Trites et al. 1993, Marogel-Popa et al. 2019, Patel et al. 2024). According to Silva et al. (2019), planting caused leg discomfort in 56% of workers, while fertilization and herbicide application caused shoulder discomfort in 41% and 56% of workers, respectively. Productivity of willow planting operations, on the other hand, depends largely on factors such as the machine capability to cover several rows, and the share of machine planting functions during the work. In practice, it is common for a machine to be used as a carrier, while the effective planting is either supported by devices fed manually by the workers, or directly by manual work (Bush et al. 2015, Manzone et al. 2017, Borz et al. 2019, Talagai et al. 2020).

Small-scale practitioners located in Romania, and probably elsewhere, have been using a simple technical solution for willow planting that consists of a farm tractor used to drag a wheeled steel frame which is typically equipped with two seats. A description of the equipment can be found in Borz et al. (2019b) and in Talagai et al. (2020). Although the workers are carried by the machine, they are required to take the cuttings from boxes located in their front and to insert them into the soil. These are actions characteristic of manual work that requires a high pace and frequency of movements. In particular, the back is frequently bent and twisted in a dominant direction, and the arms are used intensively. As a result, this may be challenging for the body in terms of physical strain, and it may increase the risk of developing musculoskeletal disorders. In forest operations, physical strain and difficulty of work are commonly evaluated based on heart rate measurements (e.g. Kirk and Sullman 2001, Magagnotti et al. 2012, Cheţa et al. 2018, Borz et al. 2019b, Marogel-Popa et al. 2019, Patel et al. 2024), as an accepted alternative to the use of rather sophisticated laboratory-based measurements and equipment. In addition, heart rate measurements can accommodate the mobility of the subjects and the measurement constraints generated by the working environment.

Given the intensive use of upper limbs when manually inserting the willow cuttings into the soil, the working hypothesis of this study was that partly mechanized willow planting operations would be characterized by a high work intensity. Accordingly:

Physical strain was evaluated in terms of cardiovascular workload by accounting for the main tasks and workplaces used in willow planting

Characterization of the job in terms of physical strain was done by running the study on a reasonable sample of workers (subjects), based on informed consent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Location and Data Collection

The data supporting this study were collected in 2017, near the Poian village located in the Covasna County, close to the center of Romania (Fig. 1). The operations were carried out by six workers (hereafter subjects), who planted in teams of two on each of the two tractors that were monitored for four days (April 26 to 29). During this time, the heart rate of the subjects was recorded by two Polar V800 devices. The used devices feature a set composed of a smart watch equipped with a wire-based computer communication system; during recording, the watch is connected via Bluetooth® technology to a heart rate monitoring sensor mounted on a strap that is adjusted on the pericardic region of the subject's body. The device may be used to setup and record a given activity in terms of location and heart rate measurements. The collected data can be visualized on a computer or on a smart device, by transferring it from the watch to a web platform; this is done by physically connecting the watch to a computer and synchronizing the data using the Polar FlowSync® software. From the web platform, the data can be exported in formats compatible with Microsoft® Excel, as well as .GPX and/or .TCX files, which are compatible with GIS software.

The time spent by the subjects on different working tasks, as well as the size of the operated plots was difficult to control in order to have a balanced number of observations per task and per subject. The devices were setup to record GPS documented data at a rate of one second, and the data was transferred to the web platform from where it was exported as .CSV, .GPX and .TCX files. The heart rate data were collected based on an informed verbal consent, and the subjects were informed about the goal of the study and the intended use of the data. They agreed to wear the devices under an identity non-disclosure clause, which was stated verbally. As a group, however, all of them empowered the researchers running the study to disclose and to use their general personal data such as the information on gender, range of their age and the main anthropometric data. The persons in charge of collecting field data instructed the workers to carry on their jobs as usual and asked for the above-mentioned data. At the time of field data collection, an ethical approval was not required by the organizations of the authors.

Fig. 1 Study location: (a) location of the study area at the national level, (b) examples of GPS locations collected at the work preparation facility (1), during relocations (2) and during planting (3), (c) an example showing the planting procedure; (d) a general view on the planting equipment. Note: the maps from (a) and (b) were created in the open source (QGIS software 2023) by using freely available vector datasets of the country and the open access Bing aerial data as of October 10, 2023, loaded by the functionalities of QGIS

2.2 Experimental Design and Data Processing

The .TCX files were imported into Garmin BaseCamp software, which enabled the visualization of the locations recorded during the study, as well as the data on GPS speed, time, and heart rate. All the data was then moved into a Microsoft Excel sheet, where it was grouped by features, coded based on the main tasks as observed in the field, and checked in the Garmin BaseCamp software. This supposed a detailed paired second-level analysis of the data from Microsoft Excel and Garmin BaseCamp having as an outcome a dataset in which each entry had specific codes to indicate the subject (hereafter coded as a, b, c, d, e or f) and the observed task. Table 1 gives more details on the tasks observed in this study.

Table 1 Description of the tasks observed in the field

|

Work task (Abbreviation) |

Number of observations |

Description |

|

Facility work (F) |

6076 |

Work carried out at the garaging facility, consisting of preparing the equipment and the cuttings for planting |

|

Headland work (H) |

66,145 |

Work carried at the headland such as moving the stock of cuttings, resupplying the boxes, maneuvers done by equipment to exit from and enter into the planting rows, and some breaks |

|

Maneuvers (M) |

3321 |

Maneuvers done by the equipment to relocate at the headland of each plot as well as other maneuvers except those from headland work |

|

Planting (P) |

137,434 |

Effective planting, while seated, meaning that the subjects took small bunches of cuttings from a box and inserted them piece by piece into the soil as the planting equipment moved forward |

|

Relocation (R) |

8476 |

Events of driving the equipment and transporting the subjects from the garaging facility to the field and between the plots in the field |

|

Delays (S) |

12,220 |

Events observed as stops into the plot while operating in a given row |

Based on the attributed codes, the data was further cleaned and sorted to enable the extraction of the statistics needed to characterize the task-based heart rate response of each subject, the heart rate response at the task level irrespective of the subject, and the heart rate response of each subject irrespective of the task. The first dataset was used to characterize the variability in heart rate response among the subjects for the same task, the second dataset served for the characterization of the tasks in terms of cardiovascular response irrespective of the subject, and the third dataset was used to characterize the cardiovascular response of each subject irrespective of the task. Data cleaning was mainly aimed at removing the records that had no heart rate values, which were typically located right at the benginning and ending of a given dataset, during the time in which the data collecting devices were placed and taken down from a given subject.

Based on the data recorded for each subject, the minimum value of heart rate was taken and conventionally used as the observed heart rate at rest (hereafter HRr) as described, for instance, in Borz et al. (2019b) and Cheţa et al. (2018). This parameter is considered to be slightly biased as compared to the measurements done while sleeping (Toupin et al. 2007). However, taking the measurements on subjects while sleeping is often impossible and, in fact, several other protocols have been accepted and used as a compromise to estimate the heart rate at rest, such as estimating it from a controlled resting period at the beginning of observation (Magagnotti and Spinelli 2012, Toupin et al. 2007), taking it from the first couple of seconds recorded for a given subject (Ottaviani et al. 2011), or by selecting the minimum value between the recordings of a controlled resting period and the minimum value recorded during the working day (Stampfer et al. 2010). In specialized scientific studies dealing with heart rate measurements, the heart rate at rest (HRr) was found to lie between 30 and 100 beats per minute (hereafter bpm) (i.e. Landgraff et al. 2023), and it is commonly accepted that a typical range would be 60 to 100 bpm (BHF 2023). To consider possible variations as compared to the minimum recorded values at the subject level, data analysis (see Section 2.3) was implemented by accounting for a HRr range of 60 to 100 bpm.

2.3 Data Analysis

Data analysis consisted of checking normality of data by means of a Shapiro-Wilk test, followed by the development of the main descriptive statistics such as the minimum, maximum, mean, median and standard deviation values. The mean and standard deviation values were used to describe the data at four levels: overall data, overall data per task, overall data per subject, and at the level of a subject involved in a given task.

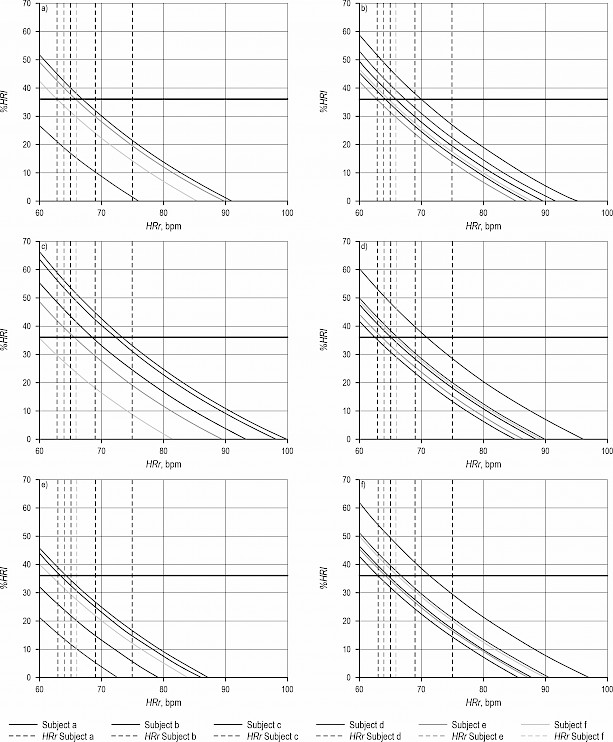

Workload was evaluated based on the heart rate increment (Eq. 1) using the classification proposed by Grandjean (1980). One advantage of the heart rate increment (hereafter %HRI) is that it makes no assumptions on the subjects' age, making it useful in studies that are constrained by the availability of the subjects' age data. Also, it has been used as an alternative to benchmark the difficulty of work in other specialized studies (e.g. Silayo et al. 2010, Cheţa et al. 2018). Eq. (1) was applied over the data coming from each subject involved in a given task, over the data coming from each task irrespective of the subject, and over the data coming from each subject, irrespective of the task.

Where:

%HRI heart rate increment

HRw heart rate at work

HRr heart rate at rest taken as the minimum heart rate found in the data of each subject, as well as in the range of 60 to 100 bpm with a step of 1 bpm when accounting for possible variation in HRr.

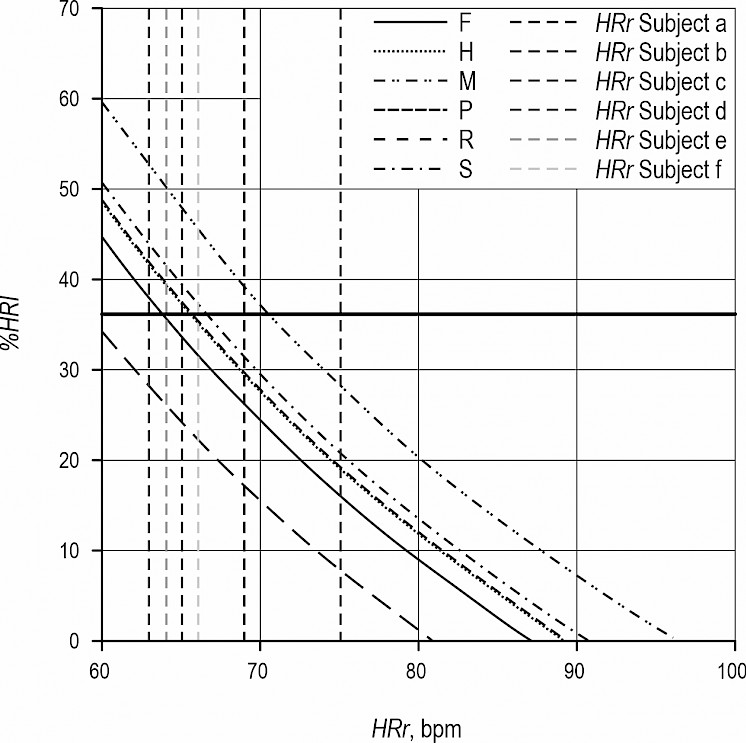

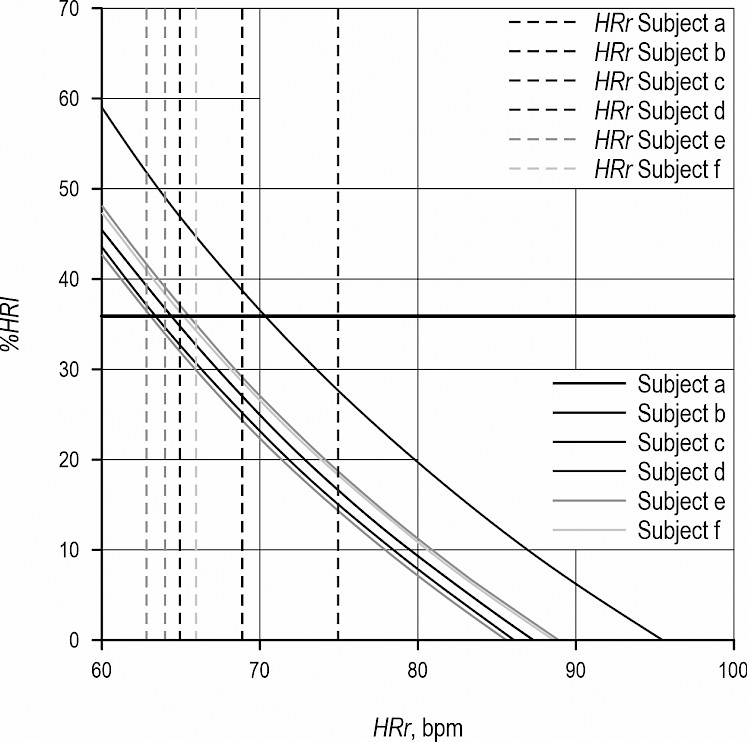

As a final step, the %HRI metric was plotted against the HRr in the range of 60 to 100 bpm. This was done with the help of Microsoft Excel, by adding minimum values of the heart rate taken from each subject's data pool as markers, and by fixing the thresholds of very low, low, moderate, high, very high, and extremely high workloads measured in terms of %HRI according to Grandjean (1980). Accordingly, a %HRI of 0, 0 to 36, 36 to 78, 78 to 114, 114 to 150, and over 150% indicate very low, low, moderate, high, very high, and extremely high workloads, respectively. The software used for statistical analysis was the Microsoft Excel equipped with the Real Statistics add-in.

3. Results

3.1 Description of Data

Table 2 gives an overview of the number of observations used in this study. The data covered 64.91 hours, of which close to 60% of the time was observed during effective planting, followed by headland work, which accounted for close to 30%. Inter-subject proportions on tasks were relatively well preserved in the data, with a dominance of effective planting (51.32 to 66.32%) and headland work (21.78 to 33.22%). Excluding the data coming from subjects b and d, the amount of data used was well balanced, covering between approximately 12 and 14 hours (Table 2).

The pool of subjects was composed of five males and one female, aged between 30 and 45 years, who weighed in between 50 and 70 kg; they were 150 to 170 cm tall. When asked, none of the subjects declared to be aware of any serious health condition, particularly those related to the cardiovascular system. Although they used to work in various farming tasks, all of them had an experience of at least 3 years in willow planting operations, and were selected from a very limited population of workers carrying on such operations in the country.

None of the datasets used in this study passed the normality test. Table 3 gives the main descriptive statistics of the heart rate response in terms of mean and standard deviation values. At the subject level, a clear differentiation of the mean heart rate was that of the subject c, accounting for more than 95 bpm. Similarly, at the task level, maneuvering and relocation were found to be in contrast with the remaining tasks.

Table 2 Number and share of observations on subjects, tasks, and job

|

Subject |

Number and share of observations per task1 |

Total (Share) |

Subject level share, % |

|||||

|

F |

H |

M |

P |

R |

S |

|||

|

a |

– (0.00) |

11,485 (26.41) |

47 (0.11) |

28,845 (66.32) |

1174 (2.70) |

1941 (4.46) |

43,492 (100.00) |

18.61 |

|

b |

2513 (13.65) |

5182 (28.15) |

56 (0.30) |

9448 (51.32) |

749 (4.07) |

463 (2.51) |

18,411 (100.00) |

7.88 |

|

c |

1629 (3.64) |

9749 (21.78) |

2352 (5.26) |

26,106 (58.33) |

2150 (4.80) |

2772 (6.19) |

44,758 (100.00) |

19.15 |

|

d |

1532 (5.00) |

6816 (22.28) |

– (0.00) |

19,230 (62.85) |

1380 (4.51) |

1641 (5.36) |

30,599 (100.00) |

13.10 |

|

e |

270 (0.57) |

16,661 (35.08) |

520 (1.09) |

25,516 (53.72) |

1574 (3.32) |

2953 (6.22) |

47,494 (100.00) |

20.33 |

|

f |

132 (0.27) |

16,252 (33.22) |

346 (0.71) |

28,289 (57.83) |

1449 (2.96) |

2450 (5.01) |

48,918 (100.00) |

20.93 |

|

Total |

6076 |

66,145 |

3321 |

137,434 |

8476 |

12,220 |

233,672 |

100.00 |

|

1 Note: tasks are described in Table 1: F – working at the garaging facility, H – work at the headland, M – maneuvering, P – planting, R – relocation, S – delays. Relative frequencies on subjects and tasks are given with decimals |

||||||||

Table 3 Number and share of observations on subjects, tasks, and job

|

Subject |

Mean and standard deviation value of heart rate (bpm) per task1 |

Overall, per subject |

||||

|

F |

H |

M |

P |

R |

||

|

a |

– |

89.77±8.15 |

93.40±4.94 |

86.66±5.51 |

86.24±11.72 |

87.54±6.81 |

|

b |

91.11±7.45 |

87.31±9.36 |

98.25±2.73 |

85.08±3.52 |

79.35±6.39 |

86.35±6.95 |

|

c |

91.08±6.43 |

95.41±7.49 |

99.80±5.53 |

96.27±5.64 |

87.42±5.86 |

95.71±6.56 |

|

d |

76.07±9.81 |

91.80±10.27 |

– |

90.00±8.61 |

72.69±7.19 |

88.96±10.21 |

|

e |

89.61±6.71 |

85.52±7.90 |

89.34±13.25 |

86.57±5.41 |

72.48±4.69 |

85.83±7.11 |

|

f |

85.47±2.37 |

88.09±8.84 |

81.58±6.86 |

89.34±6.39 |

84.21±9.89 |

88.74±7.55 |

|

Overall, per task |

87.12±10.11 |

89.13±9.11 |

96.15±9.67 |

89.38±7.13 |

80.82±10.07 |

89.10±8.26 |

|

1 Note: tasks are described in Table 1: F – working at the garaging facility, H – work at the headland, M – maneuvering, P – planting, R – relocation. In each cell, the first figure stands for the mean value, and the last value stands for the standard deviation value; S – delay data not given herein |

||||||

Effective planting was similar to headland work in terms of mean heart rate response. For a comparison of these tasks in terms of description, the reader is referred to Table 1. Relocation accounted for the lowest values, mainly because no active work was involved in this task. The minimum values found in the heart rate data of the subjects were 69 (subject a), 65 (subject b), 75 (subject c), 63 (subject d), 64 (subject e) and 66 bpm (subject f), respectively.

3.2 Cardiovascular Workload

Fig. 2 shows the plots developed to characterize the workload in terms of heart rate increment (%HRI) by considering the subjects involved in given tasks, thresholds delimiting the workload categories and the markers showing the minimum values of heart rate at the subject level. The heart rate increment was plotted in the range of 60 to 100 bpm considered for the heart rate at rest. As shown, a common characteristic was that none of the subjects experienced high, very high, or extremely high workloads, irrespective of the task. Panel a in Fig. 2, for instance, shows the %HRI curves of the subjects b to f observed at the garaging facility, along with the markers pointing their minimum heart rate that was used conventionally as the heart rate at rest (HRr). Similar to other panels in the figure, subject c had the highest HRr value, accounting for 75 bpm, as well as the highest HRw values, but still, the experienced workload was low.

Fig. 2 Heart rate increment by considering the subject and the work task: (a) work at the facility, (b) work at the headland, (c) maneuvering, (d) planting work, (e) relocation, (f) delays. Legend: %HRI – heart rate increment, HRr – heart rate at rest, curves given as continuous lines stand for the variation in %HRI, vertical dashed lines stand for the minimum values of heart rate taken as HRr for each subject, and the horizontal continuous black line stands for the threshold between low and moderate intensity work

Subject d, on the other hand, had the lowest HRr value (63 bpm), accounting for a %HRI of about 20%, being similar to subject c. As a fact, based on the recorded values of minimum HRr (63 to 75 bpm), most of the tasks were supposed to have a low to moderate intensity of work for the subjects (%HRI threshold of 36%) since none of the curves passed the threshold of 78% for the given range of HRr.

Fig. 3 shows a similar pattern based on the aggregation of data at the task level. Here, for instance, relocation would probably feel like a low workload for all of the subjects, which would also be the case of the work at the garaging facility, effective planting and headland work, delays, and maneuvering, assuming a heart rate at rest in between 65–100, 67–100, 68–100 and 71–100 bpm, respectively. Below the minimum values of these ranges, the workload would probably have been experienced as moderate.

Fig. 3 Task based heart rate increment. Legend: %HRI – heart rate increment, HRr – heart rate at rest, curves given as black lines stand for the variation in %HRI, vertical dashed lines stand for the minimum values of heart rate taken as HRr for each subject, and the horizontal continuous black line stands for the threshold between low and moderate intensity of work; F – working at the garaging facility, H – work at the headland, M – maneuvering, P – planting, R – relocation, S – delays

Finally, Fig. 4 gives an overview of the heart rate increment based on the data aggregated at the subject level by disregarding the task. It shows the closeness of heart rate increment curves for five of the six subjects under study, and mainly leads to the same observation that the workload they experienced was low to moderate. These findings indicate that the typical work tasks of manual willow planting do not expose the workers to high cardiovascular workloads. There is a differentiation between workers based on their own cardiovascular activity, as well as between the tasks, but overall, the partly-mechanized planting of willow seems to be characterized by a low to moderate workload.

The subject-based heart rate increment is shown in Fig. 4 by keeping the same mode of data visualization. Excluding the subject c, which stands apart by a %HRI curve pointing a higher cardiovascular workload when assuming a range of 60 to 70 bpm for the HRr, the rest of the data was rather grouped, indicating similar trends irrespective of the subject under consideration. At the subject level, and based on the minimum values of the heart rate extracted from the data, the work was categorized as being of low to moderate intensity.

Fig. 4 Subject based heart rate increment. Legend: %HRI – heart rate increment, HRr – heart rate at rest, curves given as continuous lines stand for the variation in %HRI, vertical dashed lines stand for the minimum values of heart rate taken as HRr for each subject, and the horizontal continuous black line stands for the threshold between low and moderate workload

Although the %HRI curve of the subject c indicated a different behavior, the work was still included in the category of low intensity based on the minimum heart rate value. Assuming a range of 60 to 70 bpm for the heart rate at rest, the work would have been perceived as moderate in intensity. Then, for a heart rate at rest of 30 bpm, which seems to be highly unrealistic for subjects carrying on physically demanding tasks on a regular basis, the cardiovascular workload would have been perceived as very high.

4. Discussion

There are many factors controlling the cardiovascular activity, such as the gender, age, health condition, and type of activity. In addition, cardiovascular response depends on the size and type of the engaged muscles, working position, pace of doing the work, and environmental conditions; also, based on the heart rate response, light and moderate work typically return heart rate responses in the range of up to 90, and between 90 and 110 bpm, respectively (Åstrand et al. 1986). Based on these figures, as well as on the heart rate increment data presented herein, the willow planting as observed in this study could be categorized as light to moderate intensity work, which did not confirm our hypothesis. However, this may come as a surprise since the effective planting typically involves the use of lower-sized muscle groups, such as the arms, used at a high pace. Based on the GPS data collected for all the subjects, the movement speed of the equipment during the effective planting was estimated at a mean value of 0.33 meters per second (supporting data not shown herein). For a planting distance between the cuttings inserted into the soil of 50 to 70 cm (i.e., Borz et al. 2019a), back and arm muscles used for planting would be active at an average pace of approximately 0.5 Hz, that is once in two seconds. However, during the effective planting, the subjects worked from a sitting position, which may be the main reason for controlling the heart rate response and keeping it at a mean value close to 90 bpm. This is also supported by the average values of the cardiovascular response in events such as relocation (close to 80 bpm), in which the subjects were found mainly to be seated without carrying on any work. This response in heart rate is close to that obtained in controlled conditions for a sitting position (Šipinková et al. 1997), although it also accounts for some of the cardiovascular recovery period, in which a given amount of time is needed for the heart rate to slow down to the resting pace. However, the time needed for recovery depends on the intensity of exercise, with some pointing out that, for intense activities, 30 minutes would not be sufficient for a full recovery (Javorka et al. 2002). This provides another hint pointing to the validity of categorizing the work as low to moderate, as the average heart rate response during the effective planting (close to 90 bpm) was only by about 10 bpm higher compared to that of tasks such as relocation (close to 80 bpm), and by 23 bpm higher compared to the average value of the minimum observed heart rate of the subjects (67 bpm). For example, a change of about 10 bpm may correspond very well to a simple change in position from lying to sitting, without any active work (Javorka et al. 2002); therefore, the mean difference of about 13 bpm can be attributed to the active work of planting.

There was a variability in the heart rate response of the subjects, which may come from their individual features and fitness for physical work. This can be seen in the data characterizing the subject c, which stands well apart from the rest of the group. As the data shows, however, the willow planting work will still remain in the domain of low to moderate intensity for the considered subjects and for a variation in heart rate at rest ranging between 60 and 100 bpm. This supports the classification of the work as low to moderate intensity, despite potential uncertainties in baseline heart rate figures, meaning that for the subjects under study, the assumption of a low to moderate intensity work holds true, while for other potential subjects, data on heart rate at work would be further required for an accurate classification. Related to this, and to the characterization of the work, this study was based on a reasonable sample of subjects that come from a very limited pool of individuals carrying on willow planting operations.

The dominant tasks, as observed in the data, were the effective planting and headland work. Due to the characteristics and performance of the equipment used, irrespective of their further implementation, they will still remain dominant in similar willow planting applications, meaning that the outcomes related to the estimation of work intensity will be mainly shaped by these two events. For example, in this study they accounted for close to 90% of the observations and returned heart rate values that were similar and close to 89 bpm. This means that the outcome of evaluations of work intensity is mainly driven by the effective planting and headland work, and the contribution of other tasks to the outcomes may be seen as marginal.

This study made no assumptions on the biomechanical workload and postural risks, and the subjects were not asked about how comfortable or tired they felt before and after the work. Also, the study did not evaluate the exposure to other harmful factors such as noise and vibration. The questions on whether this job may lead to body pain, or to risks of developing musculo-skeletal disorders remain open and worth pursuing by dedicated studies. This is mainly because this kind of work involves a frequent bending and twisting of the back, which are events that occur in a dominant direction, and by doing so, they require the use of the same muscle groups. This study used a limited number of subjects, and follow-up studies are welcome to further check and validate the findings reported herein. If the problem were studied further, it would be useful to design and run protocols so as to be able to document the heart rate response at rest during sleeping, as well as the maximal heart rate of the subjects, thus enabling the use of other metrics characterizing the intensity of work, such as the heart rate reserve (e.g. Kirk and Sullman 2001, Stampfer et al. 2010, Ottaviani et al. 2011, Magagnotti and Spinelli 2012, Cheţa et al. 2018). Until then, this study stands as a fair evaluation of the workload in partly-mechanized willow planting operations, pointing out that such jobs are low to moderate in intensity.

5. Conclusions

Based on the cardiovascular response, partly-mechanized willow planting operations are characterized by a low to moderate intensity of work. There is a variability in response that comes from the intrinsic features of the subjects but, overall, this kind of operations seems to be compatible with the human cardiovascular capabilities, validating their sustainability from this point of view. Future studies should consider the evaluation of other parameters under the umbrella of ergonomics such as the biomechanical exposure, and the exposure to noise and vibration. Among these parameters, biomechanical exposure and exposure to noise could be pritoritized, given the characterisitcs of interaction between the workers, machine, and working objects. Biomechanical exposure, for instance, could be helpful in checking if and how the characteristics of the work may affect the health of the workers since this work is carried out with a lot of back bending and twisting. It would be interesting to check the exposure to noise since the subjects typically work in open air, close to the engine of the machine.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Nicolae Talagai, Dr. Marius Cheţa and Eng. Ovidiu Tudoran for their help during data collection and processing. Also, the authors would like to thank the Department of Forest Engineering, Forest Management Planning and Terrestrial Measurements, Faculty of Silviculture and Forest Engineering, Transilvania University of Brasov, for providing the infrastructure and the equipment used to carry out this study. Some of the activities related to this research were supported by two grants of the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research, CNCS – UEFISCDI, project number PN-IV-P8-8.1-PRE-HE-ORG-2023-0141 and project number PN-IV-P8-8.1-PRE-HE-ORG-2024-0186, within PNCDI IV.

6. References

Åstrand, P.O., Rodahl, K., 1986: Textbook of Work Physiology. Physiological Bases of Exercise, 3rd ed.; van Dalen, D.B., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign: IL, USA; 501–502 p., 0-07-100114-x.

Baker, P., Charlton, A., Johnston, C., Leahy, J.J., Lindegaard, K., Pisano, I., Prendergast, J., Preskett, D., Skinner, C., 2022: A review of Willow (Salix spp.) as an integrated biorefinery feedstock. Ind. Crops Prod. 189: 115823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115823

BHF, 2023: What is a normal pulse rate? Available at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/heart-matters-magazine/medical/ask-the-experts/pulse-rate (accessed 27 October 2023).

Borz, S.A., Niţă, M.D., Talagai, N., Scriba, C., Grigolato, S., Proto, A.R., 2019a: Performance of small-scale technology in planting and cutback operations of short-rotation willow crops. Trans. ASABE 62(1): 167–176. https://doi.org/10.13031/trans.12961

Borz, S.A., Talagai, N., Cheţa, M., Chiriloiu, D., Gavilanes Montoya, A.V., Castillo Vizuete, D.D., Marcu, M.V., 2019b: Physical strain, exposure to noise and postural assessment in motor-manual felling of willow short rotation coppice: Results of a preliminary study. Croat. J. For. Eng. 40(2): 377–388. https://doi.org/10.5552/crojfe.2019.550

Bush, C., Volk, T.A., Eisenbies, M.H., 2015: Planting rates and delays during the establishment of willow biomass crops. Biomass Bioenergy 83: 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2015.10.008

Cheţa, M., Marcu, M.V., Borz, S.A., 2018: Workload, exposure to noise, and risk of musculoskeletal disorders: a case study of motor-manual tree felling and processing in poplar clear cuts. Forests 9(6): 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9060300

Dickmann, D.I., 2006: Silviculture and biology of short-rotation woody crops in temperate regions: Then and now. Biomass Bioenergy 30(8–9): 696–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2005.02.008

El Kasmioui, O., Ceulemans, R., 2012: Financial analysis of the cultivation of willow and poplar for bioenergy. Biomass Bioenergy 43: 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.04.006

Ericsson, K., Rosenqvist, H., Ganko, E., Pisarek, M., Nilsson, L., 2006: An agro-economic analysis of willow cultivation in Poland. Biomass Bioenergy 30(1): 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2005.09.002

Grandjean, E., 1980: Fitting the task to the man: An ergonomic approach; Taylor and Francis Ltd.: London, UK; 205 p.

Guidi, W., Pitre, F.E., Labrecque, M., 2013: Short rotation coppice of willow for the production of biomass in eastern Canada. In Biomass Now: Sustainable Growth and Use, London, UK, IntechOpen; 421–448 p., 978-953-51-1105-4

Heinimann, H.R., 2007: Forest operations engineering and management – the ways behind and ahead of a scientific discipline. Croat. J. For. Eng. 28(1): 107–121.

Javorka, M., Žila, I., Balhárek, T., Javorka, K., 2002: Heart rate recovery after exercise: relations to heart rate variability and complexity. Braz. J. Med. Bio. Res. 35(8): 991–1000. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0100-879x2002000800018

Kirk, P.M., Sullman, M.J.M., 2001: Heart rate strain in cable hauler choker setters in New Zealand logging operations. Appl. Ergon. 32(4): 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-6870(01)00003-5

Kuzovkina, Y.A., Volk, T.A., 2009: The characterization of willow (Salix L.) varieties for use in ecological engineering applications: Coordination of structure, function and autecology. Ecol. Eng. 35(8): 1178–1189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2009.03.010

Landgraff, I.K., Meyer, H.E., Ranhoff, A.H., Holvik, A.H., Talsnes, M.M., 2023: Resting heart rate, self-reported physical activity in middle age, and long-term risk of hip fracture. A NOREPOS cohort study of 367,386 men and women. Bone 167: 116620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2022.116620

Livingstone, D., Smyth, B.M., Cassidy, R., Murray, S.T., Lyons, G.A., Foley, A.M., Johnston, C.R., 2023a: Reducing the time-dependent climate impact of intensive agriculture with strategically positioned short rotation coppice willow. J. Cleaner Prod. 419: 137936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137936

Livingstone, D., Smyth, B.M., Sherry, E., Murray, S.T., Foley, A.M., Lyons, G.A., Johnston, C.R., 2023b: Production pathways for profitability and valuing ecosystem services for willow coppice in intensive agricultural applications. Sustainable Prod. Consumption 36: 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2023.01.013

Magagnotti, N., Spinelli, R., 2012: Replacing steel cable with synthetic rope to reduce operator workload during log winching operations. Small Scale For. 11(2): 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-011-9180-0

Manzone, M., Balsari, P., 2014: Planters performance during a very Short Rotation Coppice planting. Biomass Bioenergy 67: 188–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2014.04.029

Manzone, M., Bergante, S., Facciotto, G., Balsari, P., 2017: A prototype for horizontal long cuttings planting in Short Rotation Coppice. Biomass Bioenergy 107: 214–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2017.10.013

Marchi, E., Chung, W., Visser, R., Abbas, D., Nordfjell, T., Mederski, P.S., McEwan, A., Brink, M., Laschi, A., 2018: Sustainable Forest Operations (SFO): A new paradigm in a changing world and climate. Sci. Total Environ. 634: 1385–1397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.084

Marogel-Popa, T., Cheţa, M., Marcu, M.V., Duţă, C.I., Ioraș, F., Borz, S.A., 2019: Manual cultivation operations in poplar stands: A characterization of job difficulty and risks of health impairment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16(11): 1911. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16111911

Mola-Yudego, B., Gonzales-Olabarria, J.R., 2010: Mapping the extension and distribution of willow plantations for bioenergy in Sweden: lessons to be learned about the spread of energy crops. Biomass Bioenergy 34(4): 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2009.12.008

Norbury, M., Phillips, H., Macdonald, N., Brown, D., Boothroyd, R., Wilson, C., Quinn, P., Shaw, D., 2021: Quantifying the hydrological implications of pre- and post-installation willowed engineered log jams in the Pennine Uplands, NW England. J. Hydrol. 603(part C): 126855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126855

Ottaviani, G., Talbot, B., Nitteberg, M., Stampfer, K., 2011: Workload benefits of using a synthetic rope strawline in cable yarder rigging in Norway. Croat. J. For. Eng. 32(2): 561–569.

Patel, N.K., Singh, S., Dwivedi, U., 2024: Investigation of the ergonomics and workload of farm women during in planting and weeding operations. J Sci Res Rep 30(6): 615–622. https://doi.org/10.9734/jsrr/2024/v30i62079

Silayo, D.S.A., Kiparu, S.S., Mauya, E.W., Shemwetta, D.T.K., 2010: Working conditions and productivity under private and public logging companies in Tanzania. Croat. J. For. Eng. 31(1): 65–74.

Šipinková, I., Hahn, G., Meyer, M., Tadlánek, M., Hájek, J., 1997: Effect of respiration and posture on heart rate variability. Physiol. Res. 46(3): 173–179.

Stampfer, K., Leitner, T., Visser, R., 2010: Efficiency and ergonomic benefits of using radio controlled chokers in cable yarding. Croat. J. For. Eng. 31(1): 1–9.

Stolarski, M.J., Stachowicz, P., 2023: Black locust, poplar or willow? Yield and energy value in three consecutive four-year harvest rotations. Ind. Crops Prod. 193: 116197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.116197

Sullman, M.J., Byers, J., 2000: An ergonomic assessment of manual planting Pinus radiata seedlings. Journal of Forest Engineering 11(1): 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/08435243.2000.10702744

Talagai, N., Marcu, M.V., Zimbalatti, G., Proto, A.R., Borz, S.A., 2020: Productivity in partly mechanized planting operations of willow short rotation coppice. Biomass Bioenergy 138: 105609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2020.105609

Toupin, D., LeBel, L., Dubeau, D., Imbeau, D., Biuthillier, L., 2007: Measuring the productivity and physical workload of brushcutters within the context of a production-based pay system. For. Policy Econ. 9(8): 1046–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2006.10.001

Trites, D.G., Robinson, D.G., Banister, E.W., 1993: Cardiovascular and muscular strain during a tree planting season among British Columbia silviculture workers. Ergonomics 36(8): 935–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140139308967958

Venanzi, R., Latterini, F., Civitarese, V., Picchio, R., 2023: Recent applications of smart technologies for monitoring the sustainibility of forest operations. Forests 14(7): 1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14071503

Zumpf, C., Cacho, J., Grasse, N., Quinn, J., Hampton-Marcell, J., Armstrong, A., Campbell, P., Negri, M.C., Lee, D.K., 2021: Influence of shrub willow buffers strategically integrated in an Illinois corn-soybean field on soil health and microbial community composition. Sci. Total Environ. 772: 145674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145674

© 2025 by the authors. Submitted for possible open access publication under the

terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Authors' addresses:

Prof. Stelian Alexandru Borz, PhD *

e-mail: stelian.borz@unitbv.ro

Transilvania University of Brasov

Faculty of Silviculture and Forest Engineering

Department of Forest Engineering, Forest Management

Planning and Terrestrial Measurements

Şirul Beethoven 1

500123, Brasov

ROMANIA

Assoc. prof. Ebru Bilici, PhD

e-mail: ebru.bilici@giresun.edu.tr

Giresun University

Dereli Vocational School

28902, Giresun

TURKEY

* Corresponding author

Received: October 15, 2024

Accepted: June 09, 2025

Original scientific paper